Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) represents a collection of rare, inherited disorders profoundly impacting the immune system’s ability to combat infections, often proving life-threatening.

Infants initially appear healthy, but swiftly become vulnerable to severe, recurrent infections due to deficiencies in both T and B lymphocytes, creating a critical health challenge.

This primary immunodeficiency disrupts antibody production and cellular immunity, leaving individuals defenseless against even mild pathogens, necessitating early diagnosis and intervention.

Defining SCID: A Comprehensive Overview

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) is not a single disease, but rather a heterogeneous group of rare, life-threatening genetic disorders characterized by profound defects in the immune system. Specifically, SCID is defined by the combined absence of functional T cells and, often, B cells, critically impairing both cellular and humoral immunity.

This deficiency stems from mutations in various genes essential for lymphocyte development and function. Consequently, infants with SCID lack the ability to mount an effective immune response, rendering them exceptionally susceptible to severe and opportunistic infections. These infections, frequently bacterial, viral, and fungal, can rapidly become life-threatening.

The hallmark of SCID is the inability to fight off even common, mild infections. Without a functioning immune system, infants struggle to survive beyond the first few months of life without intervention, highlighting the critical need for early diagnosis and treatment, typically involving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or gene therapy.

Historical Context: The Case of David Vetter

David Vetter, born in 1971, became tragically known as the “Bubble Boy” due to his severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). His case dramatically illustrated the devastating consequences of this rare genetic disorder and brought SCID into the public consciousness.

David lacked a functional immune system and lived for 12 years within a sterile, germ-free environment – a plastic bubble – to protect him from infections. Despite rigorous precautions, he battled numerous infections and ultimately succumbed to leukemia, a complication often associated with SCID treatment attempts.

David’s story spurred significant research into SCID, leading to advancements in diagnosis and treatment, including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and, later, gene therapy. His life, though limited, profoundly impacted the field of immunology and continues to inspire efforts to find a cure for SCID and improve the lives of affected individuals.

Prevalence and Incidence of SCID

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) is a remarkably rare disorder, impacting an estimated 1 in 58,000 to 1 in 100,000 live births globally. This low incidence underscores the challenges in research and treatment development, as patient populations for studies are inherently small.

The prevalence varies slightly depending on the specific genetic defect causing SCID, with X-linked SCID being the most common form. Approximately 70% of SCID cases are attributed to this X-linked genetic mutation. Accurate epidemiological data remains difficult to obtain due to underdiagnosis and variations in reporting across different regions.

Newborn screening programs, where implemented, are crucial for early detection and intervention, potentially improving outcomes. Without screening, diagnosis often occurs after a series of severe infections, highlighting the importance of increased awareness among healthcare professionals.

Genetic Basis of SCID

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) arises from mutations in numerous genes vital for immune cell development and function, impacting T and B cell creation.

These genetic defects disrupt lymphocyte maturation, leading to a severely compromised immune system and heightened susceptibility to infections from a very young age.

Genetic Mutations Causing SCID

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) stems from a diverse array of genetic mutations, with at least 20 different variants identified as potential causes of this life-threatening condition. These mutations typically affect genes crucial for the development and function of lymphocytes – specifically T cells and B cells – which are fundamental components of a healthy immune system.

Many SCID-causing mutations disrupt the signaling pathways necessary for lymphocyte maturation within the bone marrow and thymus. Some mutations directly impact the production of enzymes essential for DNA recombination, a critical process in generating the diversity of immune receptors. Others affect cytokine receptor signaling, hindering the proper development and activation of immune cells. Identifying the specific genetic defect is paramount for accurate diagnosis and potential gene therapy approaches, offering hope for restoring immune function in affected individuals.

X-Linked SCID: The Most Common Form

X-linked Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) represents the most prevalent form of this disorder, accounting for a significant proportion of diagnosed cases. This variant arises from mutations in the IL2RG gene, located on the X chromosome. Consequently, it predominantly affects males, as they possess only one X chromosome and are therefore more susceptible to the effects of a defective gene.

The IL2RG gene encodes for the common gamma chain, a crucial component of several cytokine receptors vital for lymphocyte development and function. A mutation in this gene disrupts signaling pathways essential for both T cell and Natural Killer (NK) cell maturation, leading to a severe deficiency in these immune cells. Females, with two X chromosomes, are typically carriers but can exhibit milder symptoms due to X-chromosome inactivation.

Autosomal Recessive SCID Variants

Autosomal recessive SCID encompasses a diverse group of genetic defects, requiring inheritance of two mutated genes – one from each parent – for disease manifestation. Unlike X-linked SCID, both males and females are equally affected. Several genes can contribute to this form, leading to varied immunological presentations.

Adenosine Deaminase (ADA) deficiency is a prominent autosomal recessive variant, causing a buildup of toxic metabolites that impair lymphocyte development. RAG1/RAG2 deficiencies disrupt V(D)J recombination, essential for generating diverse antibody and T cell receptors. Artemis deficiency similarly affects V(D)J recombination, impacting lymphocyte function. These genetic flaws result in profoundly compromised immune systems, mirroring the severity observed in X-linked SCID, but with differing genetic underpinnings.

Understanding the Immune System Deficiencies in SCID

SCID fundamentally disrupts both humoral and cellular immunity, stemming from severe deficiencies in functional T and B lymphocytes, crippling the body’s defenses.

This combined immunodeficiency leaves individuals exceptionally vulnerable to a wide spectrum of infections, highlighting the interconnectedness of immune system components.

T Cell Deficiency: Impact on Cellular Immunity

T cell deficiency is a core feature of SCID, profoundly impacting cellular immunity – the body’s defense against intracellular pathogens like viruses and certain fungi.

T lymphocytes are crucial for directly attacking infected cells, coordinating other immune responses, and regulating immune system activity; their absence leaves individuals highly susceptible.

Without functional T cells, the body struggles to control viral infections, leading to persistent and severe illnesses, often unresponsive to standard treatments.

Furthermore, the lack of T cell help impairs B cell function, exacerbating the immune deficiency and broadening the range of potential infections.

This deficiency also compromises the body’s ability to reject cancerous cells, increasing the risk of developing malignancies, making immune restoration vital for long-term health.

Essentially, the absence of T cells dismantles a critical arm of the immune system, leaving individuals exceptionally vulnerable to opportunistic infections and other immune-related complications.

B Cell Deficiency: Impact on Humoral Immunity

B cell deficiency in SCID severely compromises humoral immunity, the aspect of the immune system responsible for producing antibodies – proteins that neutralize pathogens and mark them for destruction.

Without functional B cells, the body struggles to create these crucial antibodies, leaving individuals defenseless against extracellular bacteria, viruses, and toxins.

This deficiency results in recurrent bacterial infections, particularly pneumonia and sinusitis, as the body lacks the tools to effectively clear these pathogens.

While T cell deficiency directly impacts cellular immunity, the absence of B cell-derived antibodies further weakens the overall immune response, creating a synergistic vulnerability.

Furthermore, the lack of antibody protection hinders the development of long-term immunity following infections or vaccinations, necessitating ongoing preventative measures.

Restoring B cell function, or providing antibody replacement therapy, is therefore critical for improving the quality of life and reducing the risk of severe infections in SCID patients.

Combined T and B Cell Deficiency: The Hallmark of SCID

The defining characteristic of Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) is the profound deficiency in both T and B lymphocytes, creating a devastatingly weakened immune system.

Unlike immunodeficiencies affecting only one cell type, SCID’s dual deficit eliminates both cellular and humoral immunity, leaving individuals exceptionally vulnerable to a wide range of pathogens.

T cells are crucial for directly attacking infected cells and regulating the immune response, while B cells produce antibodies for pathogen neutralization; their combined absence is catastrophic.

This combined deficiency means infants cannot mount an effective immune response to even common infections, leading to severe and often life-threatening illnesses in early infancy.

The severity stems from the interconnectedness of T and B cell function – T cells assist B cells in antibody production, and a lack of T cells hinders this process.

Consequently, successful SCID treatment necessitates restoring both T and B cell function, typically through hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or gene therapy.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of SCID

SCID infants initially appear healthy, but rapidly develop recurrent, severe infections like pneumonia, thrush, and diarrhea, typically before six months of age.

Failure to thrive and chronic infections are key indicators, signaling a severely compromised immune system requiring immediate medical evaluation.

Early Symptoms in Infants (First 6 Months)

During the first six months of life, infants with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) often present with subtle, yet critical, early indicators of their compromised immune systems. Initially, these babies may appear healthy at birth, receiving a standard newborn screening without immediate red flags.

However, as they age, a pattern of frequent and persistent infections begins to emerge. These aren’t typical childhood illnesses; they are severe and difficult to resolve. Common early signs include recurrent pneumonia, often requiring hospitalization, and chronic diarrhea that doesn’t respond to standard treatments.

Infants may also develop persistent thrush, a fungal infection in the mouth, that is resistant to antifungal medications. Skin rashes, unexplained fevers, and a general failure to gain weight or thrive are also frequently observed. These early symptoms are crucial for prompting medical investigation and ultimately, diagnosis.

Common Infections in SCID Infants

Infants diagnosed with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) are exceptionally vulnerable to a wide range of infections, often experiencing them with unusual severity and frequency. Pneumonia, caused by various bacteria, viruses, or fungi, is a particularly common and life-threatening presentation, frequently requiring intensive care.

Persistent viral infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) or adenovirus, are also prevalent, as the immune system lacks the capacity to clear these pathogens. Fungal infections, like Candida (thrush) and Aspergillus, can become systemic and invasive, posing significant risks.

Furthermore, SCID infants are susceptible to opportunistic infections – those that typically don’t affect individuals with healthy immune systems. These infections, coupled with the inability to fight off even mild pathogens, contribute to the high morbidity and mortality associated with SCID.

Failure to Thrive and Growth Retardation

A significant clinical manifestation of Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) in infants is often failure to thrive, characterized by inadequate weight gain and growth compared to age-matched peers. This stems directly from the chronic infections and the body’s immense energy expenditure fighting these illnesses, diverting resources from normal development.

Persistent diarrhea, a common symptom in SCID, further exacerbates nutritional deficiencies, hindering the absorption of essential nutrients. The constant inflammatory response also contributes to metabolic disturbances, impacting growth hormone levels and overall metabolic function.

Consequently, affected infants may exhibit noticeable growth retardation, falling behind on standard growth charts. Early recognition of failure to thrive is crucial, as it often prompts further investigation leading to a SCID diagnosis and timely intervention to support nutritional needs and overall health.

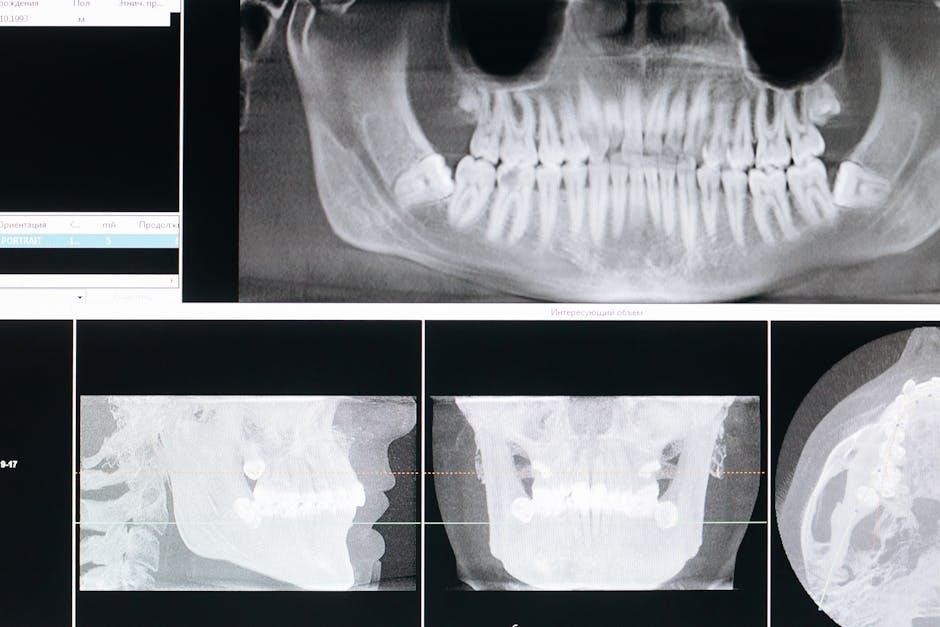

Diagnosis of SCID

Diagnosing SCID involves clinical evaluation, assessing immune function through laboratory tests, and confirming the diagnosis with genetic testing for specific gene mutations.

Early suspicion based on recurrent infections is vital for prompt testing and initiating appropriate treatment strategies for improved patient outcomes;

Initial Clinical Evaluation and Suspicion

Initial evaluation begins with a detailed medical history, focusing on recurrent or unusually severe infections, particularly pneumonia, thrush, or persistent diarrhea in the first six months of life.

A family history of similar immune problems or early childhood deaths is crucial, as SCID is often inherited. Physical examination will assess for absent or significantly reduced tonsils and lymph nodes, indicators of immune deficiency.

Pediatricians should maintain a high index of suspicion in infants presenting with failure to thrive, chronic skin rashes, or inability to gain weight appropriately. These subtle signs, coupled with infection patterns, prompt further investigation.

Prompt recognition of these clinical clues is paramount, as early diagnosis dramatically improves outcomes through timely intervention, such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or gene therapy.

Laboratory Tests: Assessing Immune Function

Initial laboratory screening typically involves a complete blood count (CBC) with differential, revealing markedly low lymphocyte counts, particularly T cells and often B cells. Quantifying immunoglobulin levels (IgG, IgA, IgM) demonstrates significantly reduced antibody production.

Further testing includes a T-cell receptor excision circle (TREC) assay, a newborn screening tool detecting the absence of recent thymic activity, strongly suggestive of SCID. Mitogen stimulation tests assess T-cell function, evaluating their ability to proliferate in response to stimuli.

B-cell function is evaluated by assessing antibody responses to vaccinations. These tests collectively provide a comprehensive picture of immune competence, guiding diagnostic pathways and treatment strategies.

Accurate and timely laboratory assessment is critical for confirming SCID and differentiating it from other primary immunodeficiency disorders, ensuring appropriate patient management.

Genetic Testing: Confirming the Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) relies heavily on genetic testing, identifying the specific gene mutation responsible for the immune deficiency. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels are commonly employed, analyzing multiple genes simultaneously associated with SCID.

These panels can detect mutations in genes like IL2RG (X-linked SCID), ADA (Adenosine Deaminase deficiency), RAG1/RAG2, and Artemis, among others. Targeted gene sequencing focuses on specific genes based on clinical suspicion.

Confirmation of a pathogenic variant establishes the genetic basis of SCID, guiding family counseling regarding recurrence risk and informing potential gene therapy approaches. Genetic testing is crucial for accurate diagnosis and personalized treatment plans.

Prenatal diagnosis and carrier screening are also available for families with a known SCID mutation, aiding in reproductive decision-making.

Treatment Options for SCID

Treatment for SCID primarily involves restoring immune function through hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or, increasingly, gene therapy, offering potential for long-term survival.

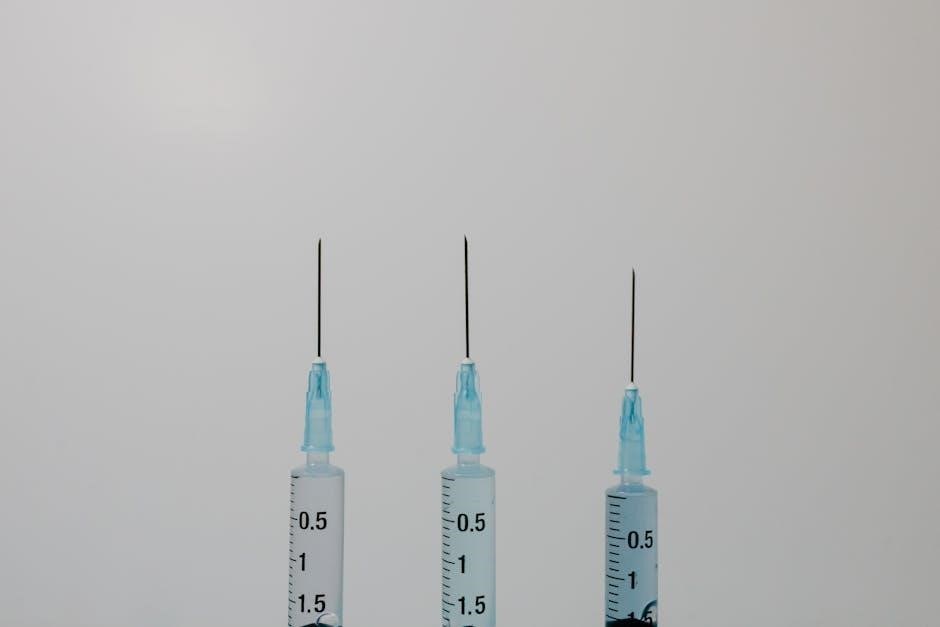

Supportive care, including infection prevention and immunoglobulin replacement, is vital while awaiting definitive treatment and managing complications.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), often referred to as a bone marrow transplant, remains the standard curative treatment for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). This procedure aims to replace the patient’s defective immune system with healthy stem cells, enabling the development of functional T and B lymphocytes.

Ideally, a matched sibling donor provides the best outcome, but unrelated matched donors or even haploidentical (half-matched) donors can be utilized. Prior to HSCT, patients typically undergo conditioning with chemotherapy, sometimes combined with radiation, to suppress the existing immune system and create space for the donor cells.

Following infusion, the donor stem cells migrate to the bone marrow and begin to produce new immune cells. HSCT carries risks, including graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), where donor immune cells attack the recipient’s tissues, and infection. Careful monitoring and immunosuppressive therapy are crucial for managing these complications and ensuring successful immune reconstitution.

Gene Therapy: A Promising Alternative

Gene therapy emerges as a compelling alternative to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for treating severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), particularly when a suitable donor is unavailable. This innovative approach involves introducing a functional copy of the defective gene into the patient’s own stem cells, correcting the underlying genetic defect.

Typically, a viral vector is employed to deliver the therapeutic gene into the stem cells, which are then re-infused into the patient after conditioning. Gene therapy has demonstrated significant success, particularly in X-linked SCID, restoring immune function and reducing the need for lifelong immunosuppression.

However, gene therapy isn’t without risks, including the potential for insertional mutagenesis – where the viral vector integrates into the genome in a way that disrupts other genes. Ongoing research focuses on refining viral vectors and gene editing techniques to enhance safety and efficacy, making gene therapy a more accessible and reliable treatment option.

Supportive Care: Managing Infections and Complications

Supportive care is crucial for infants with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), serving as a vital bridge to definitive treatment like hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or gene therapy. Prophylactic measures are paramount, including strict isolation to minimize exposure to pathogens, and preventative antibiotics and antifungals to ward off infections.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy provides passive immunity, supplementing the deficient antibody levels and reducing the frequency and severity of infections. Nutritional support is also essential, as SCID infants often experience failure to thrive. Careful monitoring for opportunistic infections, such as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, is critical.

Prompt and aggressive treatment of any infection is vital, alongside meticulous management of potential complications like graft-versus-host disease post-transplant, ensuring optimal patient outcomes and quality of life.

Long-Term Outcomes and Management

Long-term SCID management necessitates vigilant monitoring for complications post-treatment, alongside immune reconstitution assessment, and ongoing support to ensure sustained health.

Successful interventions improve quality of life, but require continuous medical oversight and proactive management of potential late effects and immune deficiencies.

Post-Transplant Complications and Monitoring

Following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), rigorous monitoring is crucial to detect and manage potential complications, which can significantly impact long-term outcomes for SCID patients.

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), where donor immune cells attack the recipient’s tissues, remains a primary concern, requiring immunosuppressive therapy and careful observation for symptoms affecting skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract.

Infections, despite immune reconstitution, pose a substantial risk due to prolonged immunosuppression, necessitating prophylactic antimicrobial medications and prompt evaluation of any febrile episodes.

Regular blood tests are essential to monitor blood counts, liver function, and kidney function, alongside assessments of immune cell reconstitution, including T and B cell numbers and function.

Long-term follow-up includes screening for secondary malignancies and endocrine abnormalities, as HSCT and immunosuppression can increase the risk of these late effects, demanding comprehensive and sustained medical care.

Immune Reconstitution and Long-Term Immunity

Successful immune reconstitution is the cornerstone of long-term survival for SCID patients following treatment, primarily hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or gene therapy.

This process involves the gradual development of functional T and B cells derived from the donor stem cells, enabling the restoration of cellular and humoral immunity, crucial for fighting off infections.

Monitoring T cell receptor repertoire diversity is vital, as a limited repertoire can indicate impaired immune function and increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections or autoimmunity.

B cell reconstitution leads to immunoglobulin production, providing humoral immunity, but antibody responses may initially be suboptimal, requiring immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Long-term immunity depends on sustained immune cell numbers and function, necessitating ongoing monitoring and potential booster vaccinations to ensure adequate protection against common pathogens throughout life.

Quality of Life for SCID Survivors

The quality of life for SCID survivors has dramatically improved with advancements in treatment, particularly HSCT and gene therapy, allowing many to lead relatively normal lives.

However, survivors often require ongoing medical care, including regular immune monitoring, immunoglobulin replacement, and management of potential long-term complications like chronic graft-versus-host disease.

Psychosocial support is crucial, addressing the emotional impact of early isolation, frequent hospitalizations, and the ongoing need for medical vigilance, fostering resilience and well-being.

Educational and social integration are vital, ensuring access to appropriate schooling and opportunities for social interaction, promoting a sense of normalcy and belonging.

Despite challenges, SCID survivors can thrive, pursuing education, careers, and fulfilling relationships, demonstrating the transformative power of early diagnosis and effective treatment.

SCID and Related Immunodeficiency Disorders

Several related disorders share characteristics with SCID, stemming from distinct genetic defects impacting immune function, requiring specific diagnostic approaches and tailored treatment strategies.

Adenosine Deaminase (ADA) Deficiency

Adenosine Deaminase (ADA) deficiency is a notable genetic defect responsible for a significant proportion of SCID cases, specifically impacting the metabolism of purines, essential components of DNA and RNA.

A deficiency in ADA leads to a toxic buildup of deoxyadenosine and its metabolites within lymphocytes, causing cellular dysfunction and ultimately, the destruction of both T and B cells, severely compromising the immune system.

This autosomal recessive disorder presents with early-onset SCID symptoms, including persistent infections, failure to thrive, and susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens, mirroring the clinical picture of other SCID variants.

Diagnosis involves measuring ADA enzyme levels in red blood cells and confirming the genetic mutation; treatment options include hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and, increasingly, gene therapy to restore functional ADA production.

Without intervention, ADA-deficient SCID is typically fatal within the first year of life, highlighting the critical need for early detection and aggressive therapeutic strategies.

RAG1/RAG2 Deficiency

Recombination Activating Genes 1 and 2 (RAG1/RAG2) deficiency represents another crucial genetic cause of Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), impacting the very process of lymphocyte development.

These genes are essential for V(D)J recombination, a critical mechanism enabling the diversification of T and B cell receptors, allowing the immune system to recognize a vast array of antigens. Mutations in RAG1 or RAG2 disrupt this process, preventing functional lymphocyte maturation.

Consequently, individuals with RAG1/RAG2 deficiency exhibit a profound lack of both T and B cells, leading to severe susceptibility to infections, mirroring the clinical presentation of other SCID forms.

Diagnosis relies on genetic testing to identify mutations in RAG1 or RAG2, while treatment options mirror those for other SCID variants – hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and gene therapy.

Early diagnosis and intervention are paramount, as untreated RAG1/RAG2 deficiency results in a fatal outcome due to overwhelming infections.

Artemis Deficiency

Artemis deficiency is a specific genetic defect contributing to Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), stemming from mutations in the DCLRE1C gene, which encodes the Artemis protein.

Artemis plays a vital role in DNA repair, particularly during V(D)J recombination – the process crucial for generating diverse T and B cell receptors. Without functional Artemis, this recombination process is severely impaired, hindering lymphocyte development.

Individuals with Artemis deficiency typically present with a classic SCID phenotype, characterized by a profound deficiency in both T and B cells, leading to extreme vulnerability to infections.

Diagnosis involves genetic testing to confirm mutations in the DCLRE1C gene. Treatment strategies, similar to other SCID forms, center around hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or, increasingly, gene therapy.

Early identification and intervention are critical for improving outcomes and preventing life-threatening complications associated with this severe immunodeficiency.